Gabrielle #28 – Too Much Blood

Sirens and vampire simps: what Robert Eggers' Nosferatu says about contemporary sexual anxieties.

SPOILER ALERT: If you haven’t seen Nosferatu and don’t want to know what happens, even though there are dozens of translations in popular culture already so you probably get the idea, you’re better off reading this after you’ve paid a visit to your local cinema complex and knocked yourself out with an Ice Blast.

I took three years of 19th century gothic literature classes at university, so basically I have a bachelor’s degree in being a fat goth. I was compelled partly by the tutor – a pipe-smoking Liverpudlian who had a coffin for a coffee table, signed off all his emails with “carpe noctem,” and once made us watch a full 90-minute episode of Most Haunted because he was in it briefly. But also because the genre serves as a transgressive outlet for the moral hang-ups of the Victorian era, which are overwhelmingly sexual in nature. You can do a lesbian reading of The Woman In White, an incestuous reading of Frankenstein, an interracial reading of Wuthering Heights. From Sheridan Le Fanu’s Carmilla to the Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, you can’t move for latent homosexuality and dangerous female desire. The entire canon stands as proof that the key to great erotic art is, unfortunately, agonising shame and repression. It’s always interesting, then, to see how these stories translate in a modern context.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula is arguably gothic literature’s greatest masterpiece. At the very least, it’s one of the most widely adapted. The original novel has layers and layers of subtext that you could pick out and zero in on, but broadly speaking it introduces the vampire (Count Dracula) as a catalyst for late-19th century fears of moral decay. Gender roles are twisted; logical men clash with hysterical ones, the archetypal mother clashes with the liberated New Woman. A threat is posed to the order of Victorian society, along with its cultural ideals, by the arrival of a “foreign” entity (it should go without saying that a lot of these fears are also racial, and race has its own relationship to sex in this context). The line between coercion and choice is blurred, and the same goes for desire and loathing. Since there was so much that couldn’t be depicted, because it would have been considered scandalous if not criminally obscene (Dracula was released a month after Oscar Wilde was imprisoned for “gross indecency”), much of the book’s sexual content is smuggled in through language, which is why there is so much “moisture” and “shivering.” Naturally, there is a lot of gay suggestion along these lines, with Stoker himself widely believed to be closeted and desperately in love with Walt Whitman.

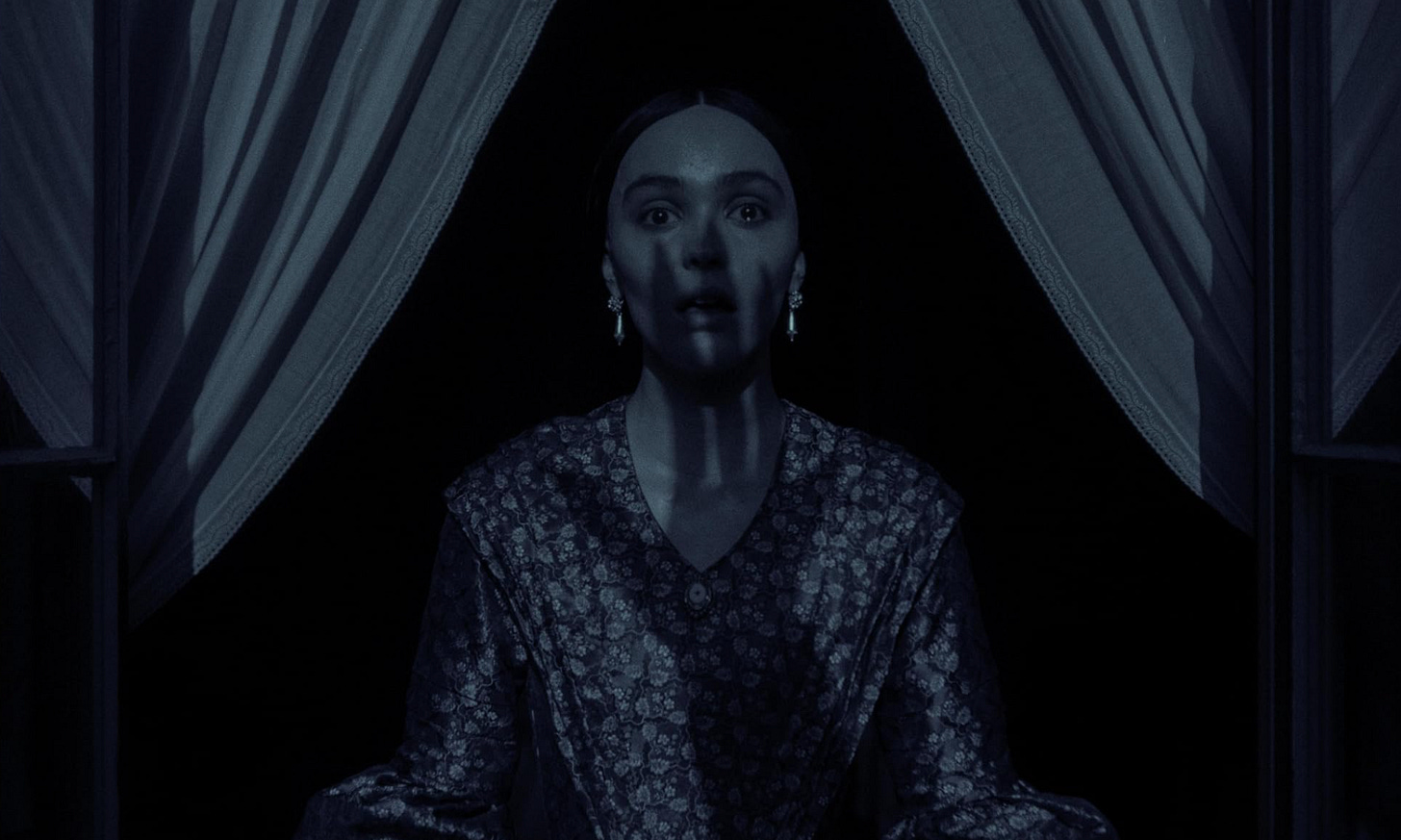

There are few current filmmakers better placed to adapt Dracula than Robert Eggers. Something of a fat goth himself, he’s no stranger to Puritan anxieties (The Witch), descents into madness (The Lighthouse), and man’s capacity for violence (The Northman). He’s also a nerd for detail and cinematography shagger, so if nothing else you know it’s going to look nuts. And Nosferatu does look nuts. The shadows are so dense they feel like things you could grab and lob at someone. The darkness has a predator’s instinct about it. The scenes in the castle near the start are shot by candlelight, making expressions appear twisted and body movements shifty. It’s pure panic writ large. As far as aesthetics go, Eggers has smashed it. The themes are slightly more confused, though it stays faithful to the book in one respect. Sex, where it appears at all, is heavily disguised.

Nosferatu is not a direct adaptation (it’s more a combination of the 1922 German expressionist film and Werner Herzog’s 1979 remake). The characters have been renamed and some condensed. It’s set in the fictional German harbour town of Wisborg, as opposed to England’s Whitby. The plot has been streamlined to eliminate all instances of women being evil, as well as most of the gay subtext (which is a shame, because if there’s one thing Nicholas Hoult excels at it’s being cunty). What we’re left with is: in the 1830s, a newly qualified solicitor visits an old Count at his castle in the Carpathian Mountains to help him purchase a house in Town Beginning With W. The Count travels by sea to Town Beginning With W, where he feeds on women and becomes the subject of a hunt that ends with his obliteration. There are at least three different sexual plot lines in the book, but Nosferatu focuses on the connection between the solicitor’s wife, Ellen (Lily-Rose Depp), and Count Orlock (Bill Skarsgård), making it a more straightforward tale of obsession.

Ellen has been besieged by erotic night terrors since childhood. Following the death of her mother, she called out to the darkness for companionship and woke Orlock from an eternal slumber. He becomes a fixed presence in her life, albeit a dark and remote one. Separated by land and sea, reality and dreams, life and death, they become each other’s greatest source of pleasure and torment. You could view this as a kind of sexual awakening on both sides, or a trauma narrative of familial abandonment and grooming. Either way, Ellen is a lonely and melancholy young girl who grows up to be a lonely and melancholy young woman. She suffers these night terrors until she marries Thomas (Nicholas Hoult), who she clearly adores. After that, she recasts her relationship with Orlok as her greatest “shame.”

When Thomas leaves for a six week trip to the Carpathian Mountains, Ellen’s terrors return. She moans and convulses violently in her sleep. Her eyes roll back and her spine arches, as if possessed. In Thomas's absence she is left in the care of their friends Friedrich and Anna Harding (Aaron Taylor-Johnson and Emma Corrin), who send for the local doctor. “Too much blood,” the doctor says. “She needs her husband!” Anna insists. Quickly, Ellen is laced into a corset, shackled to the bed, and knocked out with a chloroform rag (some girls have all the fun).

Travelling to Wisborg specifically to claim Ellen and bringing a plague of rats along with him, Orlock’s looming presence is a harbinger of destruction and deliverance in equal measure. The closer he gets, the worse Ellen’s fits become. Disgraced metaphysicist Professor Albin Eberhart Von Franz (Willem Dafoe) is the only one who views her malady as spiritual rather than medical (“Can’t you see? She is cursed!”). Meanwhile, occultist Herr Knock, Orlock’s lapdog and the estate agent who sets things in motion by dispatching Thomas to Transylvania in the first place, becomes increasingly deranged. He bites the heads off pigeons, is thrown into an asylum and murders his way out of it. One bewitched and the other mad, they both repeat the phrase: “He is coming.”

In most adaptations of Dracula, female sexuality is portrayed as a grave threat. Obviously, the reasons for that are circumstantial. It’s a reflection of (and retaliation to) social attitudes at the time. Today, that doesn’t really hold up. In Nosferatu, Ellen’s “malady” is initially perceived as disruptive – it is after all the story’s central battleground of liberation and repression, science and the supernatural, the order of man and the chaos of nature – but ultimately it becomes divine.

It’s clear throughout the film that Ellen is the heroine. Her sexuality isn’t really the problem, because she is at war with it herself. Her desire for Thomas is unwavering. She begs him not to leave, pines for him when he does, and avenges him when he returns. Besides one brief moment of hysteria, where she tears her corset open and taunts him – "You could never please me like he could” – Ellen clings to him like life itself. Her desire for Orlock, on the other hand, is suicidal (“Standing before me was death, but I’d never been so happy”). The more control he has over her, the more she longs to be free of him. He represents a dominance she doesn’t actually want. When they finally confront one another, she tilts her head up to him. “I am an appetite,” he tells her. “I abhor you,” she responds.

Things wrap up quickly from there. In order to rid the town of the plague and prevent Orlock causing further harm to those around her, Ellen sacrifices herself. Meaning, she gives herself up to him. She goes willingly. Doesn’t protest, doesn't say a word. Any loathing she had for him before has burned out. The scene of them coming together is shot like a romantic tragedy, which it essentially is. A tragedy because she does it out of love for Thomas and mankind. A romance because, in a sense, both Orlock and Ellen get what they want. They snog, he feasts on her until the sun comes up, and they die in each other’s arms. In theory that goes incredibly hard, but on screen it feels cold.

That’s partly due to the absence of struggle, but that's also what makes it interesting. A struggle would have upheld the moral lines drawn by the film early on: within the safety of marriage lies redemption, within the fire of erotic obsession lies destruction. Good vs evil, purity vs sin. Instead, these binaries are thrown up in the air. Christ-like, Ellen sacrifices herself by embracing desire; a form of self-immolation. Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil, for you are with me type shit. However, it isn’t portrayed as Ellen giving in to a desire that has been cast as depraved from the start. Rather, she transforms that desire into a siren song. Her would-be corruption becomes Orlock’s final undoing. “In heathen times, you might have been a great priestess of Isis,” Franz tells her. “Yet in this strange and modern world, your purpose is of greater worth. You are our salvation.”

Despite her suffering in life, Ellen’s death is a peaceful one. It is Orlock, in the end, whose desire drives him to ruin. He’s kind of a simp, lowkey – powerless over his own hunger, whereas Ellen uses hers against him. In that sense, Eggers’ version of the story eschews the moral hang-ups of its setting to reflect the anxieties of the 2020s. Here, it isn’t female sexual appetite that feels transgressive and dangerous, but man’s appetite for women.

Corrr I love this! Sincerely, a fat goth x

Fantastic.