Gabrielle #5 – Panties Inferno

Or; why no one can be normal about Jeremy Allen White's Calvin Klein campaign.

Part I: Authored by male evil

When Camille Paglia declared the death of the Hollywood sex symbol, she was talking about women. Her 2019 guest column for The Hollywood Reporter argues that something valuable was lost in the wake of #MeToo – a reckoning she describes as “overdue” but not without collateral damage. In this case: a film culture that, rather than seizing the opportunity to tell more challenging stories about sex, either avoided the subject entirely or flattened its complexities into a “rigid binary of oppressive political power, authored by male evil.”

The piece makes some good points (“the sex symbol as natural wonder is fading – and with her goes the internal compass of our primeval animal instincts”) and some bad ones (is this… overpopulation’s fault?). Paglia is a fun button-pusher at best but also a fantastic example of what can happen to your brain when you view life exclusively through the prism of theory, i.e. you end up defending pedophilia and attacking “Alejandro”-era Lady Gaga as “the exhausted end of the sexual revolution.” Still, her main criticism of the reductive literalism we now see on screen, resulting as a form of overcorrection and killing mystique in the process, is a solid one. Gael García Bernal made the same argument in the Criterion Closet – ironically one of the most sexless locations on Earth – recently, holding up a copy of Y tu mamá también and lamenting: “I want you to tell me which film has made you horny in the last years… there’s not many. Actually, there is none. I miss that from cinema.”

Y tu mamá también is rooted in the human mess of sex. Shot with hand-held cameras and following three teenagers ravenous for experience, it’s carnal in a way that a lot of films today, even the ostensibly erotic ones, aren’t. In Bernal’s words: you come away from it wanting “to live, and have sex, and enjoy people.” The few good erotic films that have been released recently – Benedetta, Infinity Pool, Crimes of the Future – are all body horrors and psychological dramas. In other words: they do the opposite. They’re death-driven.

Sex hasn’t been completely absent from the big screen. There’s been some decent films about sex work (Pleasure, Hustlers, Red Rocket) and the gay romance has been completely rebooted, dropping the usual pornographic lens in favour of more realistic depictions of sexual discovery (Moonlight, Portrait of a Lady On Fire, God’s Own Country, All Of Us Strangers). But the fact that it’s now considered socially unacceptable to portray a woman as an object of male desire means that heterosexual sex is as good as verboten as far as Hollywood is concerned. One of the last truly hot things I remember seeing in a box office hit is that bit in Drive when Ryan Gosling presses Carey Mulligan against the elevator wall, kisses her, and then stomps a guy’s head in.

It’s unsurprising that #MeToo led cinema down a riskless path, considering it became a cultural moment because of Hollywood. The coalition of sex and violence at the heart of erotic drama has become emblematic of the industry’s own fucked up machinations, which isn’t helped by the fact that you can sometimes draw a direct line between the two (Last Tango In Paris… many such cases). The biggest failures of #MeToo – a grassroots movement hijacked by liberal hysteria that overlooked anyone normal and mostly benefited women in C-suites, who suddenly found themselves earning six-figures as a ‘People Officer’ – were the concerns of those at the top of the entertainment industry. It tracks that the playing field of “the gender wars” would attempt to redress the balance by prioritising films about the exploitation of power (Tár, She Said, Women Talking), or films in which women wield power in a sexual vacuum (comic book, action and young adult franchises, which now account for the lion’s share of what gets commissioned).

In some ways this is progress. You only need to pick a 00s blockbuster at random to see how far Hollywood has come in terms of general politics and diversity of roles. But the function of sex on screen has changed. There is a demand, both from within the industry and from audiences, for sex scenes to lead by example. We want to be reassured that the actors are safe, and in the absence of honest conversation we crave stories that allow us to personally navigate sex from a safe distance. Again, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. That’s how you get unique if quaint stories like Good Luck to You, Leo Grande, in which a retired school teacher who’s never had an orgasm (Emma Thompson) hires a young sex worker (Daryl McCormack) to help her work through a bucket list of sexual firsts.

However, this approach caters to a repressed audience for whom sex needs to be defanged and demystified. There’s almost no space left for exploring the darker aspects of sex between men and women. Its presence is rarely joyful or matter-of-fact. There’s a growing push-back against the once largely accepted idea that things are made erotic through transgression, coupled with a fear of treating sex as something stupid – which, above all else, it is. Say what you want about gutter comedy The Sweetest Thing, but Selma Blair choking on a dick piercing while Cameron Diaz, Christina Applegate and a crowd of frontline workers try to relax her throat muscles by singing Aerosmith… that’s heterosexuality right there.

There was a moment in the early-2010s when Girls had a good thing going with their depictions of sex and nudity. As Jemima Kirke said in an interview with GQ last year: “On Girls, we thought we were doing a different version of feminism. We thought that by being less precious about our bodies, and by not thinking of them as something to hide or protect against the male gaze, that was our version of feminism at the time. And I felt it, I liked it, I agreed with it. It was not in line with what #MeToo became. It didn’t really catch on. I think our underlying, unspoken hope was that people would become more slutty. More reckless. Not reckless, reckless is the wrong word because it implies danger. But be less precious about sex.”

It’s been almost a decade since Girls ended, and women’s bodies have never been more adrift in a minefield of political discourse, shame, and can’t-say-that-anymore-because-of-woke nervousness. That’s not to say viewers are less horny. Netflix has been churning out shit erotic thrillers called things like “Burning Betrayal” and “Fatal Seduction” for years, which are the cinematic equivalent of straight-to-Kindle literary porn but nevertheless some of the platform's most-watched features. Meanwhile Hollywood, instead of engaging with heterosexual desire in more a open-minded way, has contributed significantly to the way it’s framed as inherently problematic or in need of fixing. We don’t understand sex and power any better than we did ten years ago, and the ways we treated women in the public eye before #MeToo still exist – we’ve just shifted them onto men.

Part II: Men in men's business

First came the veneration of non-threatening men. Men with twink builds and bisexual vibes. Harry Styles, Timothée Chalamet, Park Seo Joon, Pete Davidson. These are not your typically gendered sex symbols revered for their traditionally masculine qualities, like Hollywood leads of the past. These are guys who paint their nails and look like they know about rising signs and retinols. If they’re driving anyone into a frenzy, it’s usually for ‘queerbaiting’ by wearing a crop top. After that came the ‘daddy’ era of Pedro Pascal, Idris Elba, and Oscar Isaac, which tipped into the ‘babygirl’ era featuring many of the same actors plus the tortured male cast members of Succession. Occasionally someone will graduate from the James Spader school of ‘traditional good looks with alienating, slightly off key energy’ (Robert Pattinson, Alexander Skarsgård, Lakeith Stanfield), but that’s rare. More recently, we’ve seen the arrival of a new male sex symbol – or rather the original sex symbol, rebooted.

Jeremy Allen White is as classic as they come. He has brooding eyes and big arms. He smokes straight cigarettes in a white t-shirt, both on screen and off. He’s James Dean for the Huel and stick-and-poke generation; an archetypal bad boy whose breakout role (Carmy in The Bear) reinforces everything we want to project onto how he already looks. Namely: he looks like he’s got problems he doesn’t like to talk about, and he looks like he fucks. In a rare twist of over-exposure, what we know of his personal life feeds the fantasy even more (married his high school sweetheart, had two kids before 30, is making the most of fame by going on cigarette and pizza dates with Rosalia whose body language suggests she’s almost certainly topping him). The same thing happened with Paul Mescal when Normal People came out and everyone fell sick with head-loss disease whenever he went jogging around Hackney marshes wearing wired headphones and a pair of O’Neills shorts.

Both of them have a guy-you-went-to-sixth-form-with vibe that’s underscored by their performances and rooted somewhat in reality. Behind the scenes of his recent Calvin Klein campaign, Jeremy Allen White talks about how he still traverses the five boroughs by fixie bike. At the height of Normal People fever, Paul Mescal was spotted bowling out of what was surely a Tesco Express carrying a packet of prawn cocktail crisps, a bottle of Crabbies and two Gordon’s Pink G&Ts. Ben Affleck has a similar charm whenever he’s photographed fumbling a large Dunkin Donuts order. Cillian Murphy, too, is fetishised for being a media-hating family guy who doesn’t know what memes are (being online is, famously, for women and gays). This is all completely unremarkable, but with the manosphere of MRAs, PUAs, Fathers4Justice and worse looming large over every discussion of modern masculinity, they are evidence of something supposedly rare: men behaving normally. Like: look at these men, traditionally hot men, doing things that indicate basic competence and homeliness. Wow, isn’t that amazing. Behold, Ben Affleck having a high street coffee! Hark, Paul Mescal necking birds at The Old Queen’s Head in Angel like a fresher on Carnage! The elevation of Jack Graelish, with his simple personality and simply enormous legs, from footballer to star is rooted in a similar dynamic.

In a sense, Big Boys are “back.” They’re out here in films like The Iron Claw, Saltburn and The Bikeriders – shoulders broader and chests larger than ever, as if to compensate for the instability of their interior worlds. A chorus of bisexuals heard yelling “I can fix him!” at all times. But it’s not their size that’s driving people up the wall, exclusively. Male actors have been ultra-shredded for so long now it makes Marlon Brando in his prime look like Shinji Ikari. The dominance of superhero films, topless reality TV shows and gymfluencers raise the fitness bar every year, and now something like half a million men in the UK alone are addicted to steroids. The “male grooming market” is expected to be worth $115 billion by 2028; looksmaxing enthusiasts are getting their faces shattered and resculpted to look more chad; The American Society of Plastic Surgeons has reported a 99% increase in men receiving injectables in the last 20 years. For all the shit spewing out of Andrew Tate constantly, one of the most revealing things he’s ever said is “Eating sucks [...] I hate eating. I hate feeling full” – a quote so self-loathing in such a classically feminine way you could layer it over a selfie of a 16-year-old girl smoking and it would do numbers on anorexia Tumblr.

Ironically the result of all this striving for physical perfection is usually a Men’s Fitness type of look that’s mainly attractive to other men. That’s the difference, ultimately, between your Jeremy Allen White’s and your average MCU actor. It’s not about how stacked you are, but the implied means by which you got there. Jeremy Allen White looks like he got his arms by laying bricks and doing pull-ups on scaffolding. Paul Mescal actually got his thighs by playing Under-21s Gaelic football. These are men in men’s business, or so we like to believe. They have a different vibe to, say, Vin Diesel or Chris Hemsworth, who look like they spend 12 hours a week pulling cars with battle ropes – which is very impressive, but the discipline required to be Thor is of no erotic interest to most women. There’s too much maths involved in weighing protein and counting calories. Too much vanity implied by the amount of time spent at the gym. Too much focus on gaining mass (noble quest and valuable form of male bonding) at the expense of developing rizz (whatever Tony Soprano and Larry David have going on). That’s not to say one is better than the other but, in the face of overwhelming evidence, a lot of people still struggle to grasp that sex appeal does not correlate with beauty trends. There’s a reason why Jeremy Allen White is attractive to people and Andrew Tate isn’t, and it’s because one wears a vest like he can fix your sink and the other is a weird cunt who hates being alive.

The hysteria over Jeremy Allen White is a good indicator of where we’re at with sex and Hollywood. On the one hand you have journalists feeling emboldened to bring a blown-up print of one of his CK ads to the Golden Globes and asking the cast of The Bear to comment on it. Like, I’m not being funny but imagine the jail someone would be thrown in for approaching the red carpet with a cut-out of Ayo Edebiri in a sports bra. On the other hand you also have cultural commentators posting cope about how Jeremy Allen White doesn’t have a belly button, as if that knocks him down a peg. As if ‘conspicuous navel’ is a major libidinal characteristic we’ve all managed to overlook but yes, actually, now that you mention it he is a disgusting freak in need of belly button enlargement surgery.

The way we talk about sex symbols is more out of pocket, more divorced from the true nature of sex, than ever. We’re delighted to put cartoonishly horny expressions about men out there in the world, and to male actors directly. That’s fun, encouraged – professional, even! The industry can’t be seen being publicly creepy to women anymore, so being creepy to men is its replacement currency. Now we’re in a situation where men have become not only the lesser sexual threat, but the locus of our displaced prurience. Meanwhile female sexuality has become more threatening, if anything. The very suggestion of its existence is something we have to deny or repress, ostensibly for our own safety. In reality things get very violent very quickly when people don’t feel in control of their own desires, but that’s exactly how’re taught to feel when things are prohibited instead of probed. Perhaps one of the reasons we’re comfortable behaving so insanely towards men is because it feels safer to hang our desires on their physicality, even when that’s not the point.

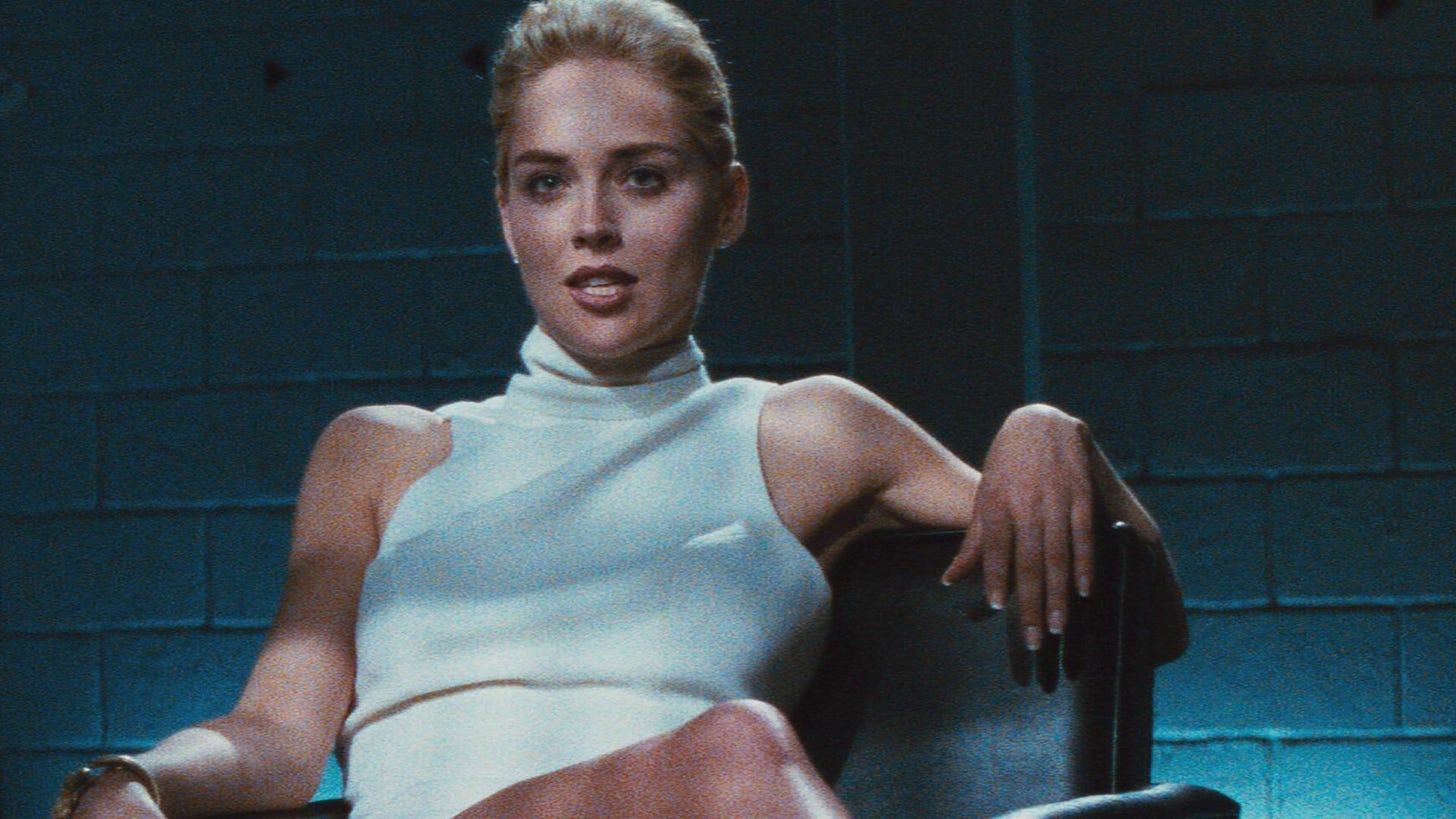

There will always be idiots looking to take this fact and twist it into permission to do whatever they want but: the most significant aspect of erotic storytelling, and of seduction itself, is non-verbal. It’s vibe, body language, reading between the lines. True erotica is a lingua ignota. It’s deeply intuitive, and therefore deeply feminine. The female sex symbol tells a different story about sex because she “commands emotional or psychological space,” as Paglia writes. “There is an unsettling aura of the uncanny around the major female sex symbols, who channel shadowy powers above or below the social realm.” The female sex symbol is disarming, hard to figure, threatening but only in the sense that what we really want from her is hidden behind a force field of her own design; the embodiment of sex itself.

I think women should be depicted as sexual terrorists driving men mental, and vice versa. Not constantly, but often. Why not? The answer to sexual violence in reality isn’t to litigate what we encounter in art or entertainment. There’s no better time to see more of the twisted erotic fantasies that, based on current porn trends, we’re indulging in all the time. Let’s see sex as slapstick more often. Let’s see it as benign. Let’s see our most incoherent impulses writ large so we can consider what it is about the death of a parent, for example, that can turn someone on.

As a culture we’re scared of sex. We’re trying to do damage control by avoiding anything that seems uncertain, that isn’t spelled out, that doesn’t involve entering into a contract and therefore contains margin for error. But, clearly, this does more harm. We’re cut off from so much life, like dogs protected by electric fencing. We’re smaller, sadder, more idiotic. If mainstream entertainment leaned into what was ailing us perhaps we wouldn’t find ourselves right here, right now, bored in a sensually bereft landscape and going to war over a pants campaign in which the star doesn’t even have a bulge. We’re not telling ourselves stories and now we are dying.

Made me howl with laughter like 4 times and nod sagely about 50. So good I upgraded to paid.

Maybe we're witnessing a kind of specialization of media functions: the sphere of pornography becomes the place where people scream and slap each other and pantomime power dynamics and sexual pathologies—sucking all of that volatile energy out of cinema, which is now possessed of a kind of post-nut clarity where it can portray people and their relations as they *ought* to be. No one has to be uncomfortably turned on by the toxic & abusive & rapey masculinity of Marlon Brando's Stanley Kowalski anymore, because that kind of prurient & problematic shit has been relegated to Pornhub categories WHERE IT BELONGS.