There’s no way anything I write could even begin to do David Lynch justice, so I might as well fire this off quick. The reason his work is beloved by so many is precisely because it articulates the inarticulable, communicates primal and arcane feelings that words fall short of. Some things can’t be explained, they can only be understood. Sometimes, when asked to elaborate, the best thing you can say is: “no.” Kyle MacLachlan put it nicely in an Instagram post (which I cannot read without turning into Kylie Minogue at Michael Hutchence’s funeral): “He was not interested in answers because he understood that questions are the drive that make us who we are.”

There are so many things you could say about David Lynch. As a director and writer, he radicalised Hollywood and then TV by doing things on his own terms and refusing to compromise (even when it backfired, because that thing is Dune). As a man, he had a unique understanding of women – what causes them to fixate or obsess; their sexual power; their innocence both in terms of the violence that strips it away, and the hell that is unleashed when it is lost (both Twin Peaks and Mulholland Drive are, to a degree, variations on the Marilyn Monroe story). As a celebrity, he never lost his honking local mechanic voice or delight in small pleasures. “Two cookies and a coke. Phenomenal.” As an artist, he took his work seriously but never himself. Who else would dedicate their life to giving shape to the most unsettling dimensions of the human experience, and then make a mental avant-garde blues album called Crazy Clown Time? Who else would embark upon the painting of a grizzly murder and title it This Man Was Shot 0.9502 Seconds Ago? Who else would direct Blue Velvet but also a 20-minute video of himself cooking quinoa in the dark?

Lynch held ground between visionary and comic, conceptual art and pop trash, masculine and boyish. A true north in a wayward world.

Windom Earle: “Garland, what do you fear most in the world?”

Garland Briggs: “The possibility that love is not enough.”

In that sense, for me, Lynch occupies the same station as Cormac McCarthy. Throughout their careers, both men were preoccupied with darkness; where it comes from, what forms it takes, and to what extent it outweighs the light. Both were hung up on the Atom Bomb in so far as it represents a tipping point for the corruption of mankind – an atrocity, wilfully created and unleashed. Both present horrors, plainly and without reserve, but with a sense of hope for things yet to be discovered.

These stances are inextricable. You can’t begin to see the beauty of the world until you have examined the full scale of its rot. You can coast through, blinkered and passionless, but you will never be properly alive. How can you know who you are until you know what you can withstand? How can you recognise a pure heart until you have sat down with evil and asked its name? The best art is stationed on the frontlines of the soul, pocket full of love letters and a full panorama of the war. Darkness is inevitable, so now what? Here, it’s worth remembering that towards the ends of their lives – McCarthy with The Passenger and Stella Maris, Lynch with Twin Peaks: The Return – both came down on the side of light. There is dread in the ceiling fan but you can still have a cherry pie that’ll kill ya, so it’s not all bad.

“I’m talking about seeing beyond fear, Roger, about looking at the world with love.” – Dale Cooper

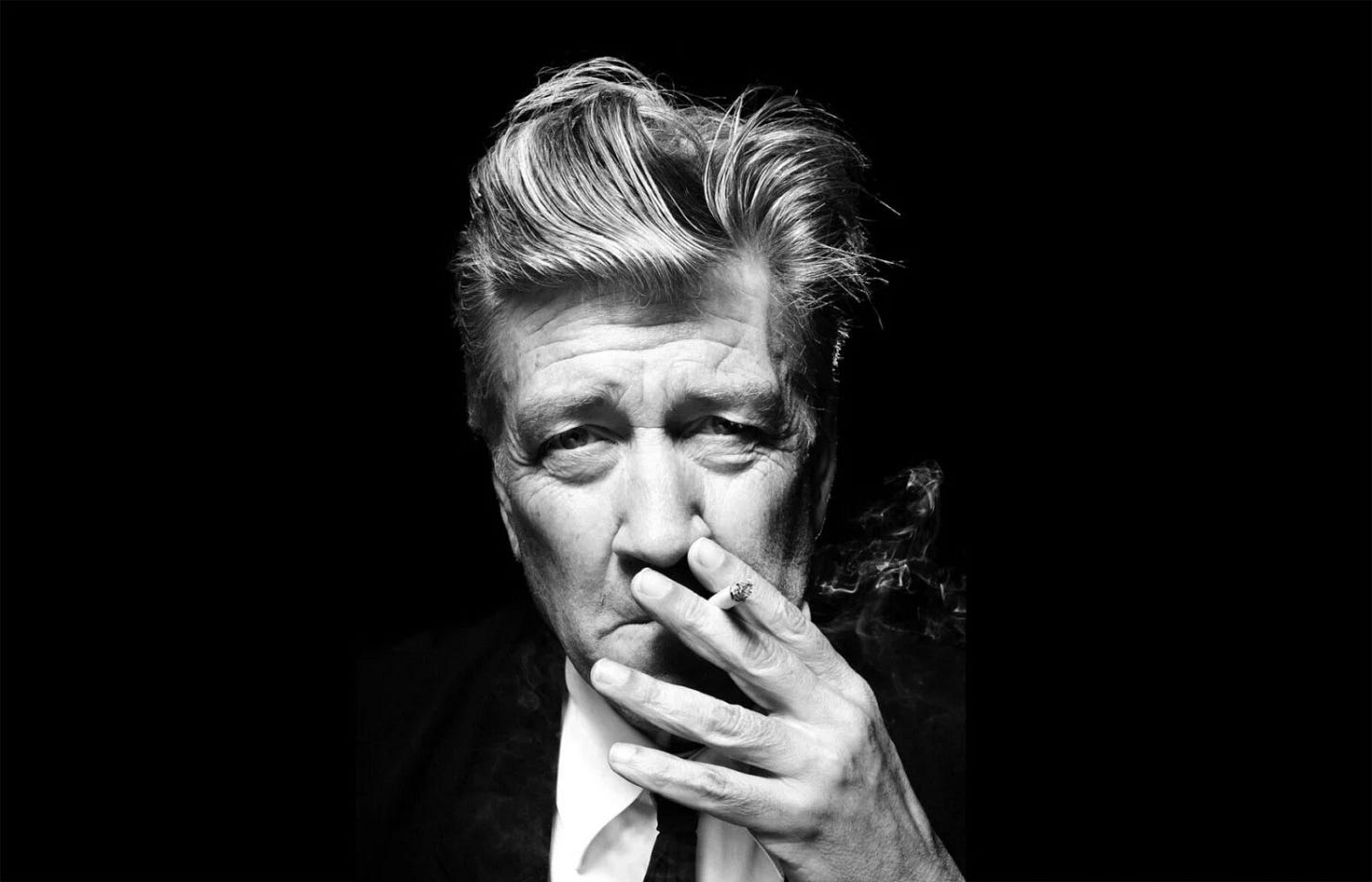

David Lynch is one of those people whose passing leaves you with the sense that a large gap has been created. Empty chair at a dinner table sensation at a Pantheon level. When someone of his influence gets taken out it feels like there is less in the world, but the world is already fuller for his passing through. And least he died doing what he loved (ripping heaters) with an astonishing head of silver hair on him. Persuasive evidence that he is, indeed, connected to the moon.

When asked about death in an interview once, Lynch likened it to a guy in a very old car. He drives it to the junkyard, sits in it for a while, then gets out and walks away. The car is the body, he said. The guy just keeps going. Here’s what he had to say on the subject in 2022 when his friend and longtime collaborator, Angelo Badalamenti, died:

“I believe life is a continuum, and that no one really dies, they just drop their physical body and we'll all meet again, like the song says. It's sad but it's not devastating if you think like that. Otherwise I don't see how anybody could ever, once they see someone die, that they'd just disappear forever and that's what we're all bound to do. I'm sorry but it just doesn't make any sense, it's a continuum, and we're all going to be fine at the end of the story.”

Strange to think that the last thing he would have seen was Los Angeles – a city he has immortalised on film better than anybody – in flames.

Thank you so much for that. Beautiful.

David Lynch taught me how to make quinoa.. that was great