Gabrielle #10 – Carry On Desiring

An interview with Lucy Roeber and Saskia Vogel of Erotic Review – the once-storied British sex mag that has relaunched as an art and literary platform exploring desire.

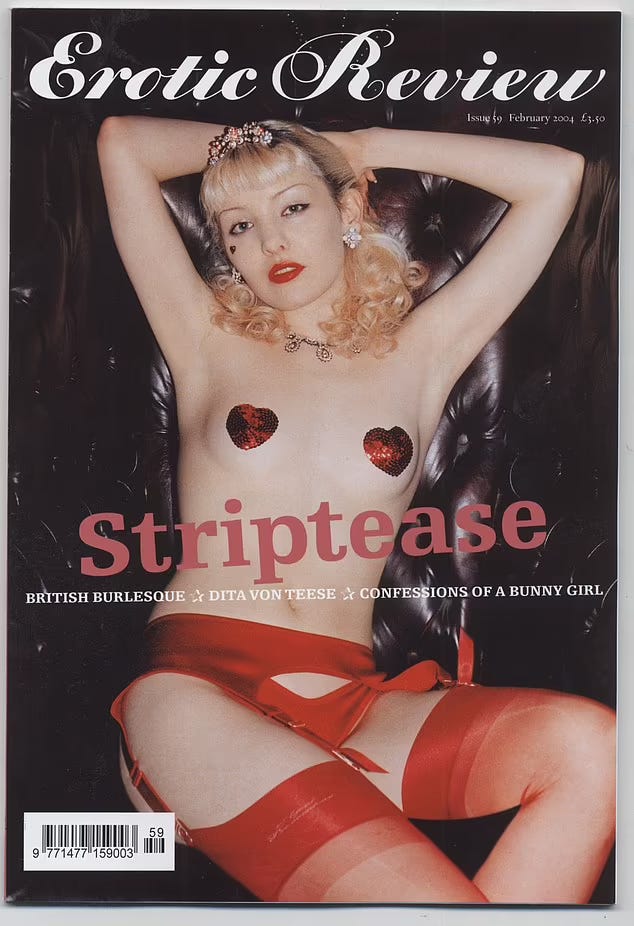

Being British and being normal about sex don’t mix. The Erotic Review, then, was always going to occupy an awkward cultural position. First published in 1997 as a bimonthly magazine, it peddled a classically Southern English mix of boarding school literary sensibilities and gutter comedy with the aim of appealing to “the primary sexual organ – the brain.” We’re talking nurse fetishes and over-the-knee spanking; illustrations of Victorian women flashing their bloomers and men with slick-back hair eating box in a tuxedo; the word “cunt” deployed in the style of Johnny Depp in that film where he plays an aristocrat poet who can’t stop shagging and dies of syphilis at 33.

Contributors at the height of its circulation included Barry Humphries (Dame Edna), Auberon Waugh (Evelyn Waugh’s son) and Alain de Botton. Rowan Pelling, who took over as editor in her early-30s and steered the publication through its most successful years, once described it as being all about “the natural and beautiful flirtatious relationship between young women and middle-aged men.” You get the vibe, right? Nabokov by way of Kent, etc.

Still, it was also one of the few relatively mainstream publications in the UK willing to publish frank and genuinely subversive writing about sex. Asked why he started the Erotic Review, founder and former editor, Jamie Maclean, said: "In the mid-90s, a lot of writing about sex was either salacious or mildly patronising – redtop or broadsheet [...] we thought it would be fun to publish a magazine where people wrote intelligently, inquiringly and amusingly about sex, to fill that gaping void between the 50s and 60s tabloid prurience and the humourless sobriety of the quality newspapers."

And it did, for a while. Despite resembling the Spectator and being aimed at the same readership, the Erotic Review was pretty funny. In 2001, at the height of the foot and mouth epidemic, they released the “Foot in Mouth” issue stuffed with bodily headlines like ‘Christine Pountney’s Swimming Pool Orgy.’ They also ran the following sketch (Lady Godiva on a horse, allegedly) and asked readers to guess the journalist responsible for drawing it (the correct answer, I’m sorry to say, is Boris Johnson).

By the mid-00s, the Erotic Review had lost its way. The decision to broaden their horizons and make an erotic magazine “not just for the toffee-nosed or the literary” (presumably financially motivated) didn’t work (presumably because it had already pigeon-holed itself as a London-centric specialist item, like Private Eye for perverts). It failed to reach a bigger audience and moved online, where it has languished for the past 15 years while ownership passed from hand to hand.

From Playboy to Loaded, every publication dedicated to the pursuit of pleasure has suffered a similar fate as the media landscape flails and cultural attitudes to sex create an atmosphere of stifled hypervigilance. Depending on your perspective, this is either the best or worst possible time to start a print publication about desire – but that’s what Erotic Review is now doing.

Relaunching as an art and literary journal, the new Erotic Review describes itself as “a platform for exploring desire as a lens on our common humanity.” Gone are the British innuendos and high society illustrations. In their place, a more international tone and a design that’s more in line with something you’d find in an indie magazine shop, sandwiched between copies of Kinfolk and BUTT. The first issue came out earlier this month and contains everything from a photo sequence from Esben Weile Kjaer celebrating the art of snogging, to a short story by Cason Sharpe about wanking over a sweet shop owner in the toilets of a dilapidated mall, to a poem by Eliot Duncan called ‘aspiring himbo’ (choice line: “alpha pussy makes hunk pregnant”) and – my personal favourite – a delirious essay by Rebecca Rukeyser titled ‘When I Miss America, I Look At r/GoonCaves.’

As far as wheelhouses go, it’s all very Gabrielle. So for this week’s newsletter I thought you’d enjoy hearing from Erotic Review’s new editors, Lucy Roeber and Saskia Vogel, who have lots of interesting things to say about desire – what it is, what we miss out on when it’s curtailed, and what Sydney Sweeney’s boobs can tell us about where the culture is at with it.

Big questions first. What’s wrong with us? More specifically: what do you think is missing from conversations about sex, or representations of sex, in culture at the moment?

Saskia Vogel (Deputy Editor): How much time do you have?

Lucy Roeber (Editor): What’s missing is seeing our desires, how they are represented and idealised as a serious, non-political subject that touches on our common humanity. A subject that isn’t pornographic or trying to sell something but touches all of us. Things still haven’t moved on from [Susan] Sontag’s famous 1967 essay on the pornographic imagination. We still consider sex an embarrassing or inappropriate subject for literary work. We are hoping to address this.

Saskia: For me personally, I want to see better researched, unbiased reporting from mainstream outlets on topics related to sex work. And I want sex worker’s voices to be heard, respected, and taken seriously in the mainstream. From restrictions on internet freedoms to what led to Roe v. Wade being overturned, sex workers have often seen it coming and called out the laws and policies that they understood would have wider implications because those laws and policies have in many cases impacted them first.

But there’s also so much right with us. So many good questions being asked and received notions being challenged. I have faith.

Do you feel there's a general lack of honesty in the way we talk about sex?

Lucy: I think it’s just that we don’t have the framework in this culture. It’s awkward and private. But a lot of unnecessary shame and confusion can breed in those silences.

Saskia: I think of it more in terms of “integrated” and “holistic.” In the countries I move in, the sexual and gender politics are varied, but one commonality is that in the mainstream culture the topic of sex is still relegated to a certain corner, bound up in ideas of decency and shame, for instance.

One of my entry points to the topic is pleasure, and within pleasure, the idea of sensation. Of course there is a difference between physical exertion when you’re taking a run and when you’re making love, but they both involve emotion, physical sensation, and so forth, and these activities give us information about the body and the self. We’re missing out on a whole body of knowledge when we tuck sex away in a special sealed off area of the human experience. How can we be honest about sex if we can’t conceive of it as part of the whole human experience?

One thing I felt reading the mag is how it deliberately isn't rooted in that British moral awkwardness around sex, or any particular cultural attitudes at all, which is maybe down to the fact that it's about desire – perhaps a more primal, universal concept? Do you think the new framing around desire helped free the new mag from some of its old constraints?

Lucy: Very much so. Desire is something that we can recognise and connect to. It isn’t about the object of your desire, but rather the feeling of it. Even if we choose to find pleasure in other ways that are not so physical. Indeed, an audio project that we are working on and launched at the party last week is a chance for people, anyone of any age and background, to anonymously record the memory of a moment when they felt desire. It’s the beginning of an audio archive. And the purpose of it is to acknowledge both the breadth and also the similarities between us in those moments.

Saskia: There’s this modernist eroticist who I’ve translated from Swedish. One of her family members shared a memory of her at … 70? 80? … visiting the opera in Stockholm. The person telling the story was a teen at the time, on a grand outing with her aunt. She remembers her aunt ascending the staircase and heads turning with desire and appreciation. It’s not about age, the writer told her niece, or even beauty. It’s about presence. It comes from within. I think about that a lot when I look around at society and our anxieties around sex and desire and how we value it, how it gets judged. Maybe with the ER’s focus on desire, we can be part of what I do think is a wider push to acknowledge the force of desire not as exclusive, but as inclusive. We can desire, we can be desired, we can love and be loved.

‘When I Miss America, I Look At r/GoonCaves’ – my favourite piece in the mag – had been passed over by a few American journals before finding its way to you. There does seem to be a reluctance to publish stories about porn and sexual subcultures from a curious point of view. They’re usually required to be moral panics or cautionary tales. What do you think we miss out on by framing porn habits in this way?

Lucy: We miss the cultural importance of pornography and subcultures by getting hysterical about them. The truth is that the porn horse bolted well over two decades ago once it became too pervasive online. We have to look at it with interest as well as questioning certain tropes within it. I love Rebecca’s essay because it looks at what it actually meant and means to the r/gooners.

Saskia: The culture is so stuck in its discourse around porn. I’m here for anything that can change that for the better. By better I mean nuanced and considered. Rebecca’s piece is brilliant in how it situates one specific aspect of pornography in a life and in longing. I’m so grateful to her for sending it our way.

Talking openly about desire means being ok with being viewed as immoral. The last five or so years have seen a big swing towards moral purity, having ‘perfect opinions’ and so on, which discourages honesty when it comes to desire because a lot of it is… wanting something you shouldn’t. I’d love to hear you both speak on your feelings on the relationship between desire and morality.

Lucy: Our desires have been led and curtailed and punished and shamed within the confines of morality for centuries. And the contemporary world is so much more open and fluid but the residue of morality still remains. The residue of what is acceptable within our particular culture. And it’s very important to acknowledge that morality is culturally specific – even to an extent within the Christian world. And one way to look at this is to open up the conversation with people around the world. We live so much more globally now that it isn’t such a leap.

Saskia: Knowing the difference between right and wrong will help us live compassionately and well together, but I think we can feel this in ourselves and by paying attention to each other. I’m suspect of moral frameworks, especially when a moral is held onto even though it may no longer serve a purpose. I’m more interested in a world where the foundation we’re on is one of a constant, steady love that holds our complexity, as opposed to a world that is shaped by a response to our fears and anxieties.

There’s more risk aversion around heterosexual sex specifically post-#MeToo, both in writing and on screen. People are understandably fearful of putting art out there that might be misinterpreted. At the same time every social media feed is just reams of explicit memes from people – younger people especially – begging to be used and abused, essentially. For weeks now Twitter has been a wall to wall discussion of Sydney Sweeney’s boobs. There’s a strange disconnect where culturally we’re kind of fine with sex as ‘content’ but not as art. Why do you think that is?

Saskia: Art invokes a deep response that we can’t always control, and sitting with how desire, longing and pleasure take shape inside us – bearing witness to that and holding it – can be discombobulating. A desire might arise that we don’t recognise or understand as something that belongs to us. Focusing on Sydney Sweeney’s boobs is a way of acknowledging this space of desire without actually having to take the risk of feeling it.

As someone who collects back issues of Playboy, I think there’s something inherently erotic about print – the physicality and inherent privacy of it, maybe. Despite the many perils of publishing at the moment, why was it important for Erotic Review to be something people can actually touch?

Lucy: It was the first decision I made about the publication when I became the editor. It had to be an object of desire. Something tactile and voluptuous to hold in your hands. Something to take with you or savour for later.

Saskia: I love that Lucy wanted the mag to be print-forward. I love paper, paper magazines, how a printed object holds its contents. I love the way our paper wiggles. I think of how I treat books and magazines, carrying them around with intention, not reading them and reading them variously. A printed magazine is something you live with in a way that you just don’t with digital.

How would you define desire?

Lucy: That is a great question! Desire shifts between the physical, emotional and mental – with varying degrees of weight. The fulfilment of our desires is connected to a belief in a transcendence, almost religious in its fervour. Yet desire is closely linked to hunger; a hunger that can be twisted, controlled and affected by life. Desire drives people to change their lives or sink into their old ones. It can be the centre of their aspirations or something to reject. Desire can be as mundane and regular as drinking a cup of tea. It is one of the most fierce and gentle forces of humanity – there is a reason why it is the subject of so much of our art.

Saskia: A human longing for connection, depth, and intimacy.

How do you think modern technology reshapes desire? Whether it's watching porn, sexting, freely posting about your exploits (me) or paying for OnlyFans – engaging in sexual activity online inherently means operating at a distance, which is kind of the ultimate erotic mode. Sometimes I wonder whether that's why we live in such horny, but unsatisfied, times. What do you think?

Saskia: Modern technology is excellent at stoking desire and it’s exciting to see the languages and modes that take shape. We’re still figuring out how to deal with all that, however. I think about the porn scholar Madita Oeming and her focus on media literacy around porn. Which is a practical solution to that discombobulation of the self that can occur through desire: a liminal state that can be chaotic, unsettling, productive, revealing. How can we equip ourselves to better meet this stimulus? A good first step, I believe, is to sit with the state of our desire and just witness it without judgement.

Lucy: Honestly, I don’t feel that we live in hornier times, although we are flooded with explicit opportunities in a way that has never occurred before. Perhaps it is dulling the intensity, perhaps not. It’s something that we want to look at in the magazine.

What are your favourite depictions of desire in art?

Lucy: I have a real soft spot for the short stories of Anais Nin, written in the 1940s, despite some of the subjects being unacceptable to modern tastes. But I love her pluralism and her openness to sensuality. The dreamlike quality of her writing.

Saskia: It’s maybe too on the nose, but Anna Calvi’s song “Desire,” Elvis Costello and Fiona Apple singing “I Want You,” so many guitar solos – Mick Ronson on “Starman,” Slash on Appetite for Destruction – Smokey Robinson’s “Cruisin’” and Bob Seger’s “Night Moves,” Caroline Polachek’s “Ocean of Tears.” Oh gosh, I’m making you a playlist. It’s one of my love languages. Jeanette Winterson’s The Passion, for variation.

To buy, subscribe to, join their monthly newsletter and generally learn more about Erotic Review, go here. You can also follow them on Instagram, where there are currently lots of excellent photos from their launch party in Soho earlier this month. Points if you can spot me looking serious and overwhelmed.